In an era flush with vaccines and antibiotics, when the greatest health risks in the developed world ride on the back of fried fish and hamburgers, it is easy to forget that infectious diseases still account for a quarter of all human deaths worldwide.

Although this is a burden largely carried by more impoverished nations, the unfolding Ebola outbreak is a dramatic reminder that infectious diseases, and the dangers they pose, have no respect for country borders.

Making the leap from animal to human

One of the greatest global health threats lies in emerging diseases, which have never been seen before in humans or – as with Ebola – appear sporadically in new locations.

Most emerging diseases are zoonoses, meaning they are caused by pathogens that can jump from animals into people. Out of more than 300 emerging infections identified since 1940, over 60% are zoonotic, and of these, 72% originate in wildlife.

Whereas some zoonotic infections, such as rabies, cannot be transmitted between human patients, others can spread across populations and borders: in 2003, SARS, a coronavirus linked to bats, spread to several continents within a few weeks before it was eliminated, while HIV has become, over several decades, a persistent pandemic.

The unpredictable nature and novelty of zoonotic pathogens make them incredibly difficult to defend against and respond to. But that does not mean we are helpless in the face of emerging ones.

Because we know that the majority of zoonoses pass from wildlife, we can start to identify high-risk points for transmission by determining which wildlife species may pose the greatest risk.

Searching for suspects

Of all wildlife species, bats in particular pose complex questions. The second most diverse group of mammals after rodents, they host more than 65 known human pathogens, including Ebola virus, coronavirus (the cause of SARS), henipaviruses (which can cause deadly encephalitis in humans) and rabies.

But they are also one of the mammalian groups most vulnerable to overhunting and habitat destruction, while providing indispensable ecological functions such as pest control by bats that eat insects, pollination and seed dispersal.

Whether eating their body weights in insects every night, or dispersing seeds from fruit trees across large areas, bats provide services to local economies worth billions of dollars across the world.

The loss of bats, whether from hunting or for disease control almost certainly would have far-reaching and long-lasting ecological and economic consequences.

This much we know, and yet the details of how zoonoses spill over from bats into people are vastly understudied. Understanding how humans and bats interact had, until recently, never been examined in West Africa, and only peripherally probed elsewhere in the world.

Uncovering behaviour that brings humans into contact with bats and other wildlife, and exposes people to zoonoses, could provide invaluable clues for preventing zoonotic outbreaks.

To address these questions, we put together an international network of collaborators, led in the UK by the Zoological Society of London and the University of Cambridge.

From Malaysia to Ghana, from Australia to Peru, bats are coming into contact with humans more and more frequently as people are expanding into previously virgin territories.

Bats as bushmeat – they didn’t ask us to eat them!

Fruit bats are also often attracted to orchards and gardens planted on the edge of their territories. But another human behaviour contributes significantly to the risk of zoonotic spillover from all wildlife species: hunting.

The consumption of bushmeat, or wild animal meat, is a global phenomenon on a massive scale – estimates of the combined bushmeat consumption in Central Africa and the Amazon Basin exceed 1 billion kilograms annually.

In Ghana, where fruit bats have tested positive for antibodies to henipaviruses and Ebola virus, the status of bats as bushmeat was essentially unknown until we began our investigation five years ago.

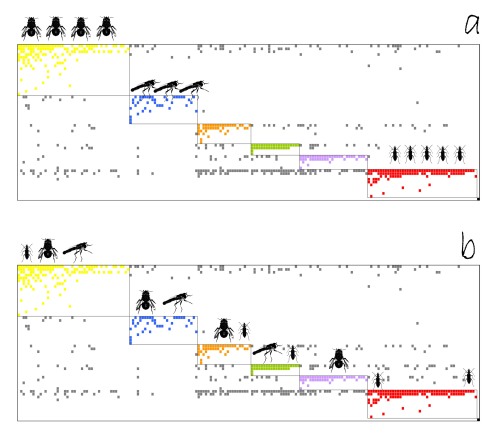

In two recent studies carried out in Ghana, we reported how many people hunt bats for both food and money. We estimated that more than 100,000 fruit bats, specifically the straw coloured fruit bat, are harvested every year.

Bat meat likely provides an important secondary source of protein for the hunters and their families, especially when other sources such as fish or antelope are scarce. Bat meat also fetches a fairly high price at markets, supplementing a hunter’s often inconsistent income.

Some people also depend on bat meat, and other bushmeat, for both their survival and livelihoods. Bushmeat hunting often occurs in remote or impoverished places, where little infrastructure exists to support alternative livelihoods or even enforcement of hunting laws.

But hunters and those who prepare bat meat for sale or consumption also place themselves at risk of exposure to bat-borne zoonotic pathogens. Such pathogens can pass through blood, scratches, bites, and urine.

Bat hunters handle live, often wounded bats and freshly killed bats, putting them into direct contact with bat blood and at risk of being bitten and scratched. Despite this, hunters are largely unaware of the risks they run.

The risks of zoonoses can be managed – but never eliminated

Understanding what risks bats pose, as little as we know, is only the beginning of the challenge. Reducing the risk of zoonoses is not simple or easy, and certainly not a simple question of stopping hunting or culling reservoir hosts.

Reducing risk sustainably and equitably will therefore likely need a combination of interventions, encompassing developmental approaches to strengthen local economies, expand job opportunities, and increase the supply of safer alternative protein sources in order to reduce the need to hunt wildlife – together with education to promote safer hunting practices.

Communities may have to change how they use land, and limit bushmeat hunting and human expansion activities to minimise the risks of spillover. At the same time, we need advances in medical technology and surveillance systems to monitor and swiftly respond when outbreaks do occur.

Such interventions can be complex and costly, but are essential. While the 2014 Ebola outbreak is the biggest to date, there will almost certainly be many zoonotic disease outbreaks in the future.

By bringing together expertise from ecology, epidemiology and social sciences, and concentrating on long-term management of risks, we hope to help communities maintain a safe and mutually beneficial relationship with their natural environment.

Alexandra Kamins is Research Analyst at the Colorado Hospital Association, and co-author of the paper ‘Uncovering the fruit bat bushmeat commodity chain and the true extent of fruit bat hunting in Ghana, West Africa’, funded by the University of Cambridge and the Gates Foundation. She works as a reacher for the Colorado Hospital Association.

Marcus Rowcliffe is Research Fellow at Zoological Society of London, and co-author of the paper ‘Uncovering the fruit bat bushmeat commodity chain and the true extent of fruit bat hunting in Ghana, West Africa’, funded by the University of Cambridge and the Gates Foundation.

Olivier Restif is Royal Society University Research Fellow at the University of Cambridge. He receives funding from the Royal Society, the BBSRC and US Federal Agencies.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.