Updated: 02/04/2025

Fig. 1. Recently metamorphosed green frog (Lithobates clamitans) at the edge of a pond (photo by Laura Martin)

Amphibians develop in watery places that are full of plants. And yet we know little about how these plants affect larval amphibians. As disease, climate change, and land-use change continue to threaten amphibian populations worldwide, it is more important than ever to understand what makes for good amphibian habitat.

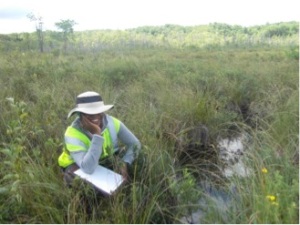

Fig. 3 Shauna-kay Rainford at Bear Swamp, NY, one of the litter collection locations(photo by Laura Martin)

In the study “Effects of plant litter diversity, species, origin and traits on larval toad performance,” Cornell undergraduate Shauna-kay Rainford (now a graduate student at Penn State University), graduate student Laura Martin, and Professor Bernd Blossey investigated how plant litter communities influence the growth and survival of Anaxyrus americanus (American toad) larvae. They reared tadpoles in singles species and litter mixtures using 15 native and 9 nonnative plant species common to central New York, USA, recording survival, time to metamorphosis, and growth rate.

Fig. 4 Microcosms in which individual larval amphibians were reared in leaf litter treatments. (photo by Shauna-kay Rainford)

Survival in single species treatments ranged from 0% (in Rhamnus cathartica litter) to 96% (Pinus strobus). Tadpoles also failed to metamorphose in Acer rubrum, Cornus racemosa, Rosa multiflora, and Tsuga canadensis. Percent metamorphosis was highest in nonnative Lonicera spp. (76.7%), native Phragmites australis americanus (73.3%), nonnative P. australis (60.0%), and nonnative Alnus glutinosa (60.0%). Interestingly, whether the plant was native or nonnative did not affect amphibian performance.

In multi-species treatments, number of plant species had no effect on larval survival or metamorphosis. However, larvae reared in mixtures of 3 species were larger than those reared in single species treatments of the same species. But increasing litter diversity to 6 or 12 species did not further improve larval survival or performance. This result is consistent with analyses that reveal that most ecological processes saturate at relatively low levels of diversity.

Currently, understanding of the relationships of biodiversity and ecosystem function is drawn largely from studies of plant communities in temperate grassland ecosystems. But the vast majority of plant material is not consumed green; it enters detrital food webs like the one studied in this experiment. This study is an important first step towards understanding the mechanisms that underlie plant-amphibian interactions. It further highlights the importance of plant traits, but not origin, when considering amphibian habitat restoration and conservation.