Updated: 23/04/2025

Find out what role predation plays in the transfer of less complex parasites in the Early View paper “The underrated importance of predation in transmission ecology of direct lifecycle parasites” by Giovanni Strona. Below is his short summary of the study:

Predation is the primary route for transmission in parasites having complex life cycles. However, despite being one of the strongest evolutionary forces, little is known about its role in the ecology and evolution of simple life cycle parasites (that is parasites that spend all of their life on a single host).

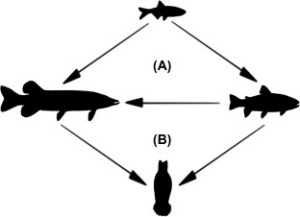

Monogeneans are one of the most abundant group of fish parasites, and are peculiar in that they do not use more than one host during their whole life. Being well investigated, they constitute a good benchmark to explore if predation has some relevance for parasites when not directly involved in transmission from one host to another. For this, I used a large dataset and different approaches to test whether predators and preys share more monogenean parasites than one would expect from their geographical distribution, habitat preference and phylogenetic relationships. It turned out that preys and predators do share more monogenean parasites than expected.

The observed overlap degree was much higher at the genus level than at the species one. This suggests that predation may play an important role in promoting monogenean host range expansion. In addition, a good proportion of considered prey-predator pairs showed a significantly high parasite overlap at the species level. This last result promotes some intriguing hypotheses. In particular it may indicate a tendency of some monogenean parasites to evolve transmission strategies more targeted towards host interactions than towards species specific traits.

Monogenean parasites identify suitable hosts on the basis of various cues related to host physiology and behavior, such as shadows, chemicals, mechanical disturbance, and osmotic changes. Usually, these cues are generated by the activity of single species, but could also result from species interactions. For example, a predator hunting a school of fish may produce peculiar water turbulence, shadows, and specific chemicals, which are stimuli that have already been demonstrated capable of inducing mass hatching in monogeneans. Some monogenean parasites could have developed the ability to identify these cues, and to infect with similar probability a predator and its prey/s. If this hypothesis was true, it would have strong implications on evolutionary ecology, suggesting the existence of a peculiar situation, where some parasites have evolved high specialized host finding behaviors to become more generalist. Morevover, it would indicate that some monogenean parasites could be more vulnerable to coextinctions than suggested by the size of their host range, as their survival would depend on that of both the prey and the predator species.